Women, War and Displacement in Antiquity

Undergraduate Research Assistant Holly Axford has been researching ancient narratives of displacement. In this blog, she writes about the representation of women displaced by war in Ancient Greek epic and tragedy.

‘By means of such genres as theatre, including puppetry and shadow theatre, dance drama, and professional story-telling, performances are presented which probe a community’s weaknesses, call its leaders to account, desacralize its most cherished values and beliefs, portray its characteristic conflicts and suggests remedies for them, and generally take stock of its current situation in the known ‘world.”[i]

Victor Turner, From Ritual to Theatre

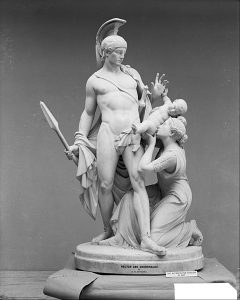

When we think of the consequences of war in the ancient Greek world, the first thing to come to mind may be the touching, yet to some, gilded, accounts of heroic death in battle of The Iliad; or perhaps the cruel fate of Astyanax, son of Hector, whom the Greeks would not allow to grow up and seek revenge for his father. Yet, for half of the population of plundered cities like Troy, the termination of conflict was only the mark of a new chapter in their suffering. Women who saw their communities defeated in war became the captives, the possessions, of the victors. Displaced from their homelands, isolated and vulnerable to exploitation, the experiences of these women were something that ancient writers were well aware of.

The Iliad, otherwise a powerful epic of martial glory, displays a clear recognition of the consequences of war for its female characters, while Athenian tragedy went even further in bringing these same women centre stage. The emotive resonance of their stories across the ancient world is clear, but they have also continued to speak to us in the present, where Euripides’s Trojan Women, in particular, has frequently resurfaced in light of contemporary parallels.

The Displacement of Women in Ancient Texts

Immortalised in The Iliad are the glory-driven exploits of its male warriors, culminating in the death of Hector, defender of Troy and its inhabitants, at the hands of Achilles. The pathos of this scene alone, as the poem’s climactic moment, is substantial, but it is significant that the audience is unable to separate Hector’s desire for glory and remembrance from the fates of his dependents.

During the meeting of Hector and his wife, Andromache, at the Schaean gates, suspended between the two worlds of battle and domesticity, Andromache makes it clear to both Hector and the poem’s audience that he is her only source of protection. In her emotive and highly persuasive speech, Andromache makes use of what J. T. Kakridis has termed the ‘ascending scale of affections’.[ii] She reminds Hector that she has ‘no father, no honoured mother’ (6.413), and goes on to recount the events of her family’s deaths, before eventually claiming: ‘Hector, thus you are father to me, and my honoured mother, you are my brother, and it is you who are my young husband’ (6.429-30).[iii] In doing so, Andromache distances herself from her blood relatives and, consequently, stresses her complete reliance on Hector.

It is made clear that, should Hector fall, Andromache will be taken as a slave to ‘work at the loom of another’ far away from Troy (6.456). An acknowledgement of this fate is therefore a necessity. Rebecca Muich, in her study of Andromache’s laments, has argued that Andromache ‘demands Hector view the situation from the perspective within the oikos, rather than without’.[iv] In this way, then, Andromache’s speech here, in addition to the poem’s concluding laments for Hector, provide an alternative vantage point from which to view the war. The poem’s main battle narrative plays out parallel to an awareness of the fates awaiting the women of Troy, confronting the consequences of war beyond the temporal scope of the narrative.

Athenian tragedy takes up these same threads and weaves them into focused and full accounts of women’s displacement.[v] Euripides’ Trojan Women – which one scholar has termed ‘an unrelenting portrait of suffering’ – is a key example of this.[vi] What makes Trojan Women such a powerful text, in my opinion, is that, albeit within its own limited context, the play allows for individualised expressions of displacement and its consequences.

‘Alas! Who shall have me, a miserable hag, for his slave? Where, where on earth shall I go, poor old decrepit Hecabe, resembling one dead, the shadowy image of a corpse? Oh, the thought of it! Shall I be set to keep watch at some doorway or given charge over children, I, who reigned as queen in Troy?’ (190-196)[vii]

Here, Hecabe’s reflection on her present circumstances is heavily coloured by her individual previous status and experiences. Stressing her own weakness, she wonders what her role will be as an elderly woman, and now a slave, in a foreign land. This highlights how a variety of personal factors, age being one example, could have influenced how women experienced displacement. Earlier, Hecabe asks ‘should I not lament when my homeland, my children, my husband are no more?’ (107-108). Her sorrow, here, comes not just from the toil and suffering of her new slave-status, but is equally the result of her separation from the world and the people whom she has always known. Displaced from the destroyed city of Troy, Hecabe seems to have lost the sense of identity which her homeland granted. With her children dead or, like her, prisoners of the Greeks, Hecabe can no longer fulfil her duty to the daughters who she ‘raised in purity to grace the arms of no common husbands’ (485). Taken from her expected role, Hecabe is displaced from the social fabric with which she is familiar. It is this sense of alienation as a consequence of warfare, just as much as the immediacy of death and the threat of sexual violence, which forms the heart of her lament.

Alongside Hecabe’s experiences, the play also explores the consequences of war for young women, mainly through its presentation of the disruption or the absence of marriage. The Trojan princess Cassandra’s perverted celebration, after being claimed as the prize of the Greek king Agamemnon, as she instructs her mother and the chorus to ‘deck my head with garlands and rejoice in my royal marriage!’ (352-353), only serves to draw more attention to the absence of this ritual within their new status as slaves and concubines.[viii] Polyxena, the youngest daughter of Hecabe and Priam, is sacrificed at the tomb of Achilles and denied this rite of passage altogether (622-623). For these women and others like them, the impact of war is not only a physical displacement from their homeland, but also their displacement from normal social rituals and institutions.

In the play, Andromache goes so far as to claim that Polyxena’s death is a ‘kinder fate’ than hers (631). As with Hecabe, it appears that Andromache considers her displacement to be a greater source of sorrow even than death – because it robs her of both identity and rights, of all that ‘home’ had made her and of control over her life. A striking feature of Andromache’s narrative is its depiction of the precarious nature of her new position following this displacement from home and family. She is removed from the protection of normal and familiar social networks, and consequently becomes wholly reliant for her safety on her captor and master, leading Hecabe to advise her to ‘honour your new lord and…offer him the enticement of your winning ways’ (698-700). Her lack of security becomes an even more prominent theme in another play of Euripides’, Andromache, which depicts her vulnerability as a slave and foreigner without connections to the spiteful attacks of Hermione.[ix]

Suspended between the destroyed city of Troy, which nonetheless continues to exercise a powerful hold over the play’s imagination, and their new, scattered homes, the Trojan women are shown to exist in a stasis which reflects their lack of personal agency. Yet, within the confines of the play, the experiences of these women are given a voice.

Why Trojan Women?

That Euripides’ Trojan Women offers a sympathetic and impactful account of women’s experiences of war and displacement is clear. But we might now wonder why this story – a story of ‘barbarian’ women – seems to have resonated so strongly with a fifth-century Athenian audience.

This blog post began with a quote from Victor Turner’s From Ritual to Theatre. Here, Turner suggests that dramatic performance can provide a framework for interrogating the issues which a community is presently facing, and at the same time allowing for a reflection on its own identity. This can be used to guide our understanding of Trojan Women.

The play has often been viewed within the context of the Peloponnesian War. Indeed, in the same year that it was produced, the city of Melos was sacked by Athenian forces, its men killed and its women and children enslaved.[x] Given these apparent historical parallels, it might be possible to interpret the play’s narrative as a direct engagement with contemporary events. Some scholars have gone so far as to identify Euripides as a pacifist, and the play as an anti-war tract in light of Athenian military atrocities.[xi] Whether or not these parallels were the deliberate aim of its author, it seems reasonable to suppose that the play’s audiences would have called to mind the conflict in which they were presently playing a part.[xii] Trojan Women, then, may or may not have been tied to a specific historical moment in Athenian history, offering its own perspective on current political decision-making.

But even more strikingly than this, the play leads its audience to reflect on the universality of the experiences which it depicts. As a result of its emotive portrayal, an Athenian audience comes to sympathise with the suffering of defeated victims.[xiii] Might the play have encouraged Athenians to think upon the possibility of themselves facing the same fate in the future, to some extent at least? What Trojan Women speaks to is not simply the ability of an author but also the willingness of audiences to recognise the suffering and the humanity of those outside their own community. Casey Duéhas undertaken a comparison between the play and modern US media coverage of the Iraq War. She notes that, while much US media coverage spoke to real, human experiences, they were from an almost exclusively western perspective.[xiv] Trojan Women, on the other hand, offers a narrative of war from the perspective of the defeated female ‘other’, instead of the victor.[xv] The audience is confronted with the reality that the death of soldiers in battle is not the only consequence of warfare. The displacement which survivors of war experience is treated equally, if not more so, as a source of sorrow and reflection, and is shown to have a drastically destabilising effect on the identity and cohesion of a community.

The Trojan Women of Today

The consequences of war and displacement for women, as expressed by the Trojan women of Euripides, are in no way relics of an ancient past. The extent to which this story still speaks to present-day experiences is evidenced by the numerous adaptations of Euripides’ play. Euripides’ Trojan Women reaches out to us across two millennia, prompting discussion and reflection on those features of displacement which are experienced most frequently by women.

One such adaptation is the Trojan Women Project. The work of filmmakers Charlotte Eager and William Stirling, alongside Syrian director Omar Abu Sada, it first brought together in a series of workshops a group of Syrian women displaced from their homeland and residing in Jordan. In what one reviewer of the opening UK performance termed ‘the most urgent work on the London stage’, the resulting production was a powerful and incredibly moving account of these women’s ordeals. Reworking the original play of Euripides to incorporate these experiences, the story of the Trojan women acts as a familiar and understandable framework from which to convey individual accounts of displacement to a wider audience.[xvi] The play is able to strike a balance between communal suffering and unique perspective; at one point in the performance, the mutual experience of the actors is stressed as they speak and step forward in unison. At other times, one individual is the clear focus, seated at the front of the stage as she tells her own story. In this way, dramatic performance becomes a tool for encouraging a sense of community, which the audience may also find themselves drawn into, without assuming one single refugee experience or painting ‘the refugee’ as a single, homogenous identity.

Femi Osofisan’s Women of Owu situates the story of Euripides’ Trojan Women in a real-life historical context. First performed in 2004 after being commissioned by the Chipping Norton Theatre, its narrative occurs following the sack of the city of Owu, in what is now Nigeria, by the two kingdoms of Ijebu and Ife after a seven-year siege. Its temporal continuities, however, go even further. A note on the play’s origins, given at the beginning of the published script, also refers to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by US led ‘Allied Forces’ – the same term which is used in the play to refer to the besieging army.[xvii] Apparently seeking to liberate Owu from tyranny, the victors’ motivations are undermined by the female chorus, one of whom highlights the violent actuality of this supposed liberation as she states: ‘after your liberation, here we are, with our spirits broken and our faces swollen’.[xviii] Nor does Osofisan shy away from acknowledging the sexual violence which the women are now at risk of.[xix] In the opening scene, the audience is directly confronted with this reality as one woman remembers how ‘our women were seized and shared out among the blood-splattered troops to spend the night’.[xx] With this, and its sense of temporal continuity, the play makes clear that the consequences of war are, for those who are most vulnerable, comparable across time.

Further Questions

The fate of the Trojan Women is a poignant tale of loss and displacement as a result of conflict. It gives voice to the experiences of women in the ancient world, so often ignored, and yet strikingly, when these women do speak it is the family, home and community identity they leave behind which forms the focus of their laments.[xxi] As Euripides and others interpreted the story of the Trojan Women against a backdrop of fifth century BCE warfare, it may now be used to reflect upon modern experiences of displacement and the ways in which we communicate those experiences.

- Would you argue that Euripides is writing a ‘pacifist’ play?

- What are the possible differences between the fates of the Trojan Women and modern experiences of displacement?

- How and to what extent are individual experiences of displacement reflected in modern media?

[i] Victor Turner, From ritual to theatre: the human seriousness of play (New York: Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982), 11.

[ii] Marilyn Arthur, ‘The Divided World of Iliad VI’, Women’s Studies 8 (1981), 29.

[iii] Quotations from Homer, The Iliad of Homer, trans. Richmond Lattimore (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

[iv] Rebecca Muich, ‘Focalisation and Embedded Speech in Andromache’s Iliadic Laments’, Illinois Classical Studies 35 (2011), 10.

[v] Laura Slatkin, ‘Notes on Tragic Visualizing in the Iliad’ in Chris Kraus, Simon Goldhill, Helene P. Foley and Jas Elsner (eds), Visualizing the tragic: drama, myth, and ritual in Greek art and literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 29.

[vi] Casey Dué, The captive woman’s lament in Greek tragedy (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006), 136.

[vii] Quotations from Euripides, Electra and Other Plays, trans. John Davie (London: Penguin Books, 2004).

[viii] Dué, 145.

[ix] Dué, 151.

[x] Dué, 148.

[xi] N. T. Croally, Euripidean polemic: The Trojan Women and the function of tragedy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 232.

[xii] Croally, 234.

[xiii] Dué, 166.

[xiv] Dué, 166-167.

[xv] It is not unique in this perspective as an ancient Greek play: Aeschylus’ play The Persians also looked at conflict and its impacts from the perspective of people whom the Greeks had been fighting.

[xvi] P. Eberwine, ‘Music for the wretched: Euripides’ Trojan Women as refugee theatre’, Classical Receptions Journal 11 (2019), 200.

[xvii] Femi Osofisan, Women of Owu (Ibadan, Nigeria: University Press PLC, 2006),vii.

[xviii] Osofisan, 12.

[xix] Olakunbi Olasope, ‘Lament as women’s speech in Femi Osofisan’s Adaptation of Euripides’ Trojan Women: Women of Owu’, Textus 30 (2017), 111.

[xx] Osofisan, 3.

[xxi] Readers might also be interested in Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls and Natalie Haynes’ A Thousand Ships, which rework Homer’s Iliad from the perspective of displaced women.