What is ‘Applied Classics’?

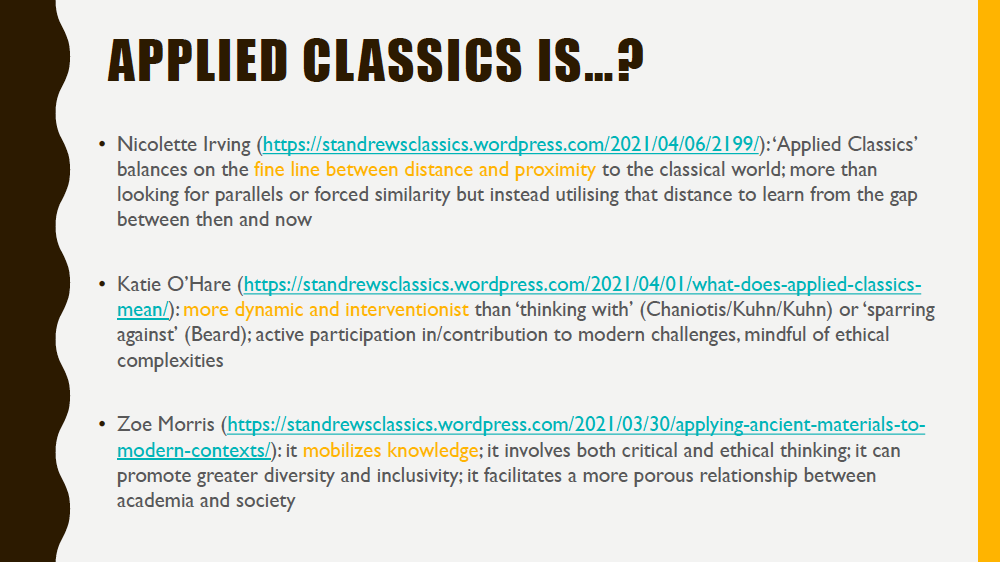

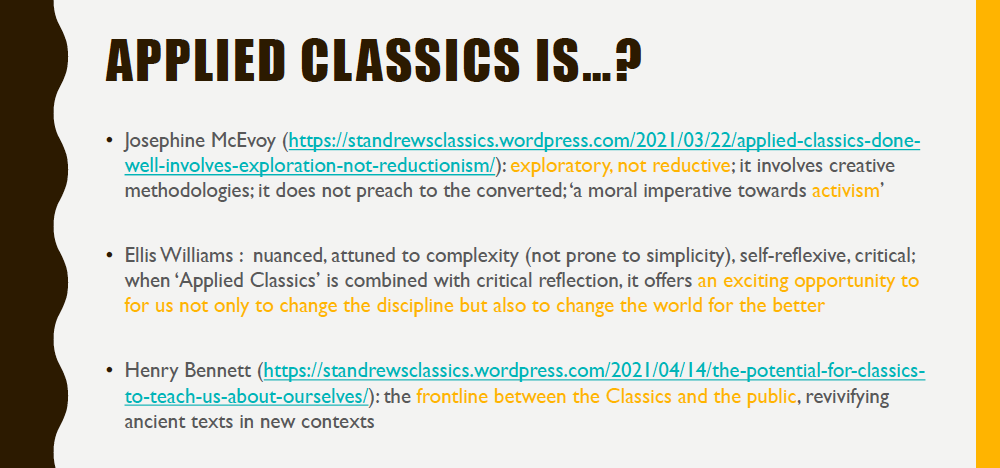

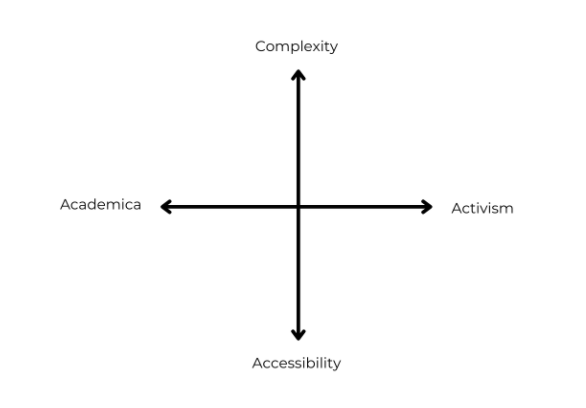

For us, ‘Applied Classics’ comprises two connected endeavours: it is the active application of ancient material to contemporary issues; and in the process, ‘Applied Classics’ plays an important role in addressing the legacy of Classics as a subject, and in challenging the many misuses of antiquity in the modern world.

‘Applied Classics’ is not a new phenomenon (as module leader Alice Konig outlines in this peer-reviewed article). As we discuss in our blogs and project pages, many inspiring scholars have been drawing on the ancient world to contribute to contemporary debates, challenges and problem-solving, in different ways and for many years. We have learnt a lot from reading books and articles by (for example) Mary Beard, Esther Eidinow, Helen Morales, and Neville Morley (a select reading list can be found here). And we have been inspired by a range of guest lecturers, who have generously shared their experiences of doing ‘Applied Classics’, such as Elena Isayev, Mai Musié, and theatre company NMT Automatics. Our research into other people’s ‘Applied Classics’ work has helped us to come up with our own definitions.

First of all, we distinguish ‘Applied Classics’ from some related phenomena: ‘public classics’ and ‘reception studies’.

Public Classics

Public Classics does valuable work in increasing access to Classics beyond the classroom and beyond the (often very privileged) demographics that normally come into contact with the subject. It can take the form of schools workshops, introducing pupils to ancient art, texts and ideas for the first time. It also happens in public lectures, via TV documentaries, in prison education, and many other contexts. (You can read an overview of recent Classical publication engagement activity in the UK here.) As well as making the study of antiquity more accessible to a wider range of people, Public Classics can help make it more diverse; everyone benefits when a wider range of people engage with the subject.

Public Classics is clearly a very positive development, then; and, quite rightly, Public Classics initiatives are well-supported with funding from organisations such as the Society for Classical Studies. That said, it also has potential pitfalls and limitations. One perennial risk is that, in sharing and promoting Greco-Roman antiquity as ‘something important to learn about’ (or even ‘something to learn from’), we might perpetuate its cultural dominance and keep the Classical world on its age-old pedestal, as some kind of paradigm for modern times. Those engaged in Public Classics need to remain wary of this (as many are!) and avoid reinforcing the colonial legacy of our subject. As several of our students, reflect:

‘Classical outreach must be conducted in a reflective and self-aware manner, with those involved continuously questioning their actions and aims.’

India Goodman

‘The way forward is by facing Classics head-on, taking responsibility and accountability for the harm Classics has caused in the past, and the danger it can still create in the wrong hands.’

Kristoffer Naas

‘The most successful endeavours are the most self-aware, and do not attempt to ‘redeem’ the study of Classics but rather to acknowledge its flaws, if not to directly solve them then at least to address them head on.’

Duncan Tarboton

‘Classical outreach’ can become ‘Applied Classics’ (as this article underlines); we are dealing with a spectrum, not a binary. But we think it is important to identify a clear distinction between ‘sharing Classics with others’ and ‘applying Classics to contemporary issues’. The former is informative, educational, often inspirational and impactful – but it is more a case of handing Classics over to others than a case of deploying it for specific purposes. Ideally, ‘Applied Classics’ is also informative, educational, inspirational and impactful; but in our view, it is also much more than that – it involves the purposeful application of carefully-chosen aspects of antiquity as a useful intervention in a contemporary challenge.

Classical Reception

‘Classical Reception Studies is the inquiry into how and why the texts, ideas, images and material cultures of Ancient Greece and Rome have been received, adapted, refigured, used and abused in different historical and cultural contexts.’

https://classicalreception.org

The study of Classical Reception is a well-established sub-discipline and has been a key component of Classical Studies from antiquity itself. Like Public Classics, it differs from our definition of Applied Classics in some important ways. In fact, one might argue that Classical Reception analyses historic examples of Applied Classics. Many of our own Applied Classics projects have a strong element of Reception study in them: an important part of the process of identifying ways to bring ancient materials into dialogue with modern issues is to explore why and how that material has been used (or misused) in the past. But we do not stop there; we move from our analysis of historic receptions and adaptations of Classical antiquity to devising and delivering adaptations, applications and interventions of our own. As one of our students, Chloe Dabbs, put it: studying Classical Reception gave her ‘all the tools and supplies to build an IKEA bookshelf but left out all the instructions of how to assemble it.’ Applied Classics is this assembly process.

To use a different analogy: while Reception Studies is a valuable form of scholarship, Applied Classics is a valuable form of ‘Citizen Scholarship’ – a branch of academia that builds bridges to activism and has tangible impacts in the wider world. Of course, pure scholarship can do this too; but citizen scholarship actively identifies specific, real-world issues to address (such as climate change, fake news, gender inequalities, racism, even the so-called ‘migration crisis’), and creatively deploys research to contribute to solutions. Crucially, Applied Classics also engages directly with stakeholders outside academia, crafting outputs (such as training programmes, interactive websites, museum activities, and so on) where ancient and modern experiences can be brought into productive dialogue. It is a dynamic, problem-solving endeavour, which seeks to draw on the many lessons we can learn from different ancient communities to help tackle pressing challenges in the 21st century.

What can we gain from Applied Classics?

‘As someone who is often attacked by older relatives and STEM-student friends who ask “what’s the point of Classics?’, I find that my justification rests on this applicability of Classics to the modern world.

Anna Pilgrim

In describing Applied Classics as a problem-solving endeavour, we do not want to suggest that it can solve every problem! On the contrary: as noted above, it is vital that we approach Applied Classics with humility and an awareness of past tendencies to ‘look up to Classical civilisation’ as a paradigm for everything. Modern challenges like climate change and fake news cannot be solved by Classicists working alone. But Classicists can contribute their particular areas of expertise (alongside environmental scientists, digital media experts, and many others) to offer fresh lenses, new perspectives on long-standing problems, and material that is valuable to think with. We do not advocate a gung-ho approach to applying Classics everywhere and anywhere – finding loose parallels between ancient and modern scenarios, or getting over-ambitious about what a Classical lens can add. But we do believe that our study of ancient societies, cultures, politics, physical environments, scientific activities (and so on) has much to offer interdisciplinary efforts to tackle different social, cultural and political challenges today.

Rather than providing us with ‘models to emulate’, antiquity offers us useful points of comparison and opportunities for critical analysis – which can productively unsettle assumptions, challenge preconceptions, and reframe how we think about (e.g.) mobility and hospitality, climate justice, or how poverty is defined and experienced by different groups. Students benefit enormously from thinking critically about what exactly a ‘Classical lens’ can contribute to any give issue; and they gain a huge range of team-based and individual skills, from thinking creatively, debating responsibly, identifying target audiences and the best media/methodologies for engaging with them, trouble-shooting obstacles, and practising outcomes-focused thinking. Along the way, they get to know the discipline of Classics like never before – and they make valuable contributions to wider debates about its future, how it should or could be studied, and why. Classics as a whole thus benefits from Applied Classics – both because ‘applying’ Classics to modern issues encourages scholars to look at the ancient world with fresh eyes, and also because it introduces a wider range of people to antiquity – and to what antiquity can do for us.

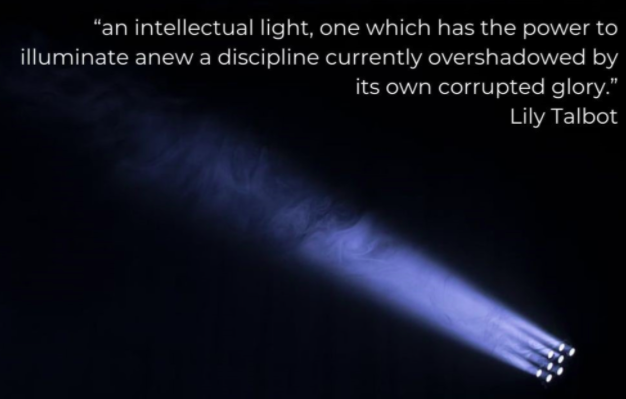

In the words of one of our students, Lily Talbot:

Applied Classics is ‘an intellectual light, one which has the power to illuminate anew a discipline currently overshadowed by its own corrupted glory.’

We hope you enjoy browsing our websites and the various Applied Classics projects which we have developed! Don’t forget to let us know what you think by sharing your feedback via our contacts page.